The croissant isn’t French — it’s an Austrian culinary rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. Since the 13th century, Austrian bakers have been shaping the croissant’s predecessor, the crescent-shaped kipferl, mimicking the Ottoman moon, which, according to popular lore, was used to celebrate the Habsburgs’ final standoff against Turkish invaders after the Battle of Vienna in 1683.

Austria’s long-standing defiance against the Turks is as integral to its national identity as Charlemagne’s victory over the Muslim Moors is to France. As Christendom’s last line of defense against Islamic expansion into Europe, Austria held the line. Yet today, Turkish kebab shops fill nearly every street in central Vienna, competing with bakeries that once symbolized the Ottoman Empire’s defeat. The contrast is striking.

Parallel societies will inevitably form without a clear path for immigrants to adopt a national identity.

The Turkish community has become Austria’s largest minority. As of 2023, approximately 500,000 residents of Turkish origin live in the country, a sharp rise from 39,000 in 2001 — a 1,200% increase.

Does this shift reflect modern-day “tolerance” ending nearly 1,000 years of imperial rivalry, or are deeper forces at work?

Tolerance or dire straits?

Popular explanations of Europe’s recent mass migration credit events like the Syrian war in 2015 or the siege of Sarajevo in the 1990s, which prompted waves of asylum-seekers. However, mass migration in Austria dates back to the aftermath of World War II, when the country lay in rubble with a diminished male population.

To rebuild, Austria sought foreign workers. With the Iron Curtain blocking labor from Eastern Europe, the former Catholic empire turned to its historical rival across the Bosphorus. Austria actively recruited Turkish workers in the following decades, promising employment and economic opportunities.

One local Turkish resident, Metin, remembers, as a child in the 1980s, seeing Austrian embassy billboards in Istanbul promoting jobs and benefits — a golden ticket. Like tens of thousands of others, his family eagerly accepted the offer. However, both Austrians and Turks miscalculated. Austrians assumed the Turks would return home when the job was over. The Turks believed they would be welcomed in their new land. Neither were correct.

“I quickly realized that I wasn’t wanted,” Metin recounted. “My work was wanted, but I wasn’t.”

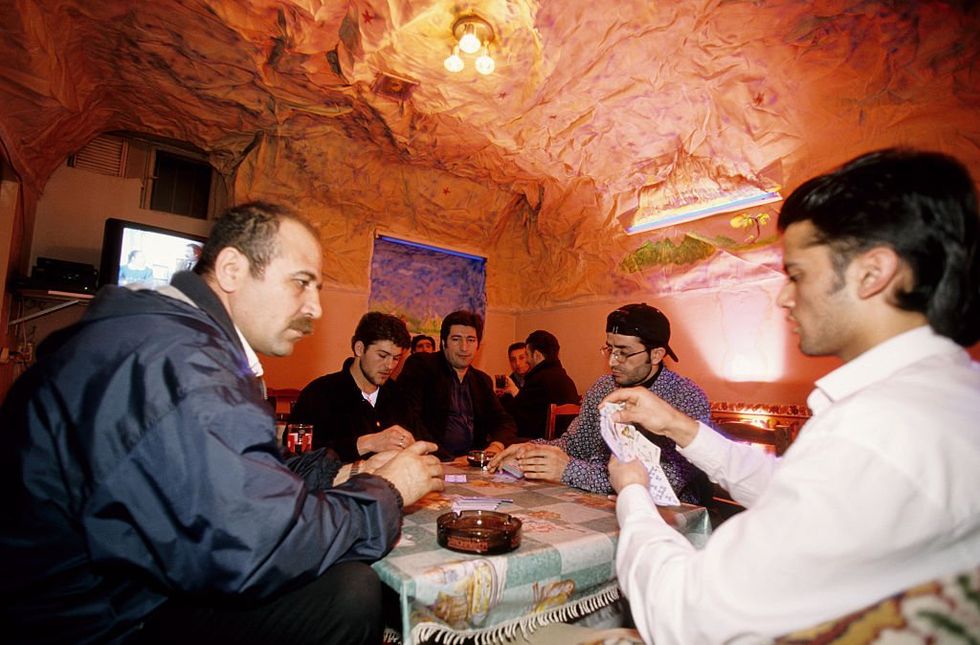

What started as a temporary workforce has transformed Austria. Turks have established their own parallel society, which continues to grow in influence and numbers. Today, Muslim immigrants, particularly from Turkey, are surpassing Austrians in birth rates while preserving a strong religious and cultural identity from their home country.

Meanwhile, the once-Catholic imperial stronghold is becoming increasingly secular, stepping away from the faith that once defined its national identity. This demographic shift has profound implications — not just for Austria but for all of Europe.

What America can learn

The United States can learn valuable lessons from countries that have dealt with mass migration for generations. Today, 14.9% of the U.S. population is foreign-born, the highest percentage since the immigration surge of 1910.

While left-leaning arguments favor foreign workers to boost the economy, the long-term challenges cannot be ignored. Postwar Austria may have benefited from such policies, but history shows that immigration requires more than economic justification — it demands integration and assimilation.

As Turkish-born Metin warns, welcoming workers means welcoming people. Parallel societies will inevitably form without a clear path for immigrants to adopt a national identity. At best, they may coexist peacefully, leaving the long-term impact dependent on demographics. At worst, clashing cultural norms could threaten national cohesion for generations.

The United States holds a key advantage over Austria in shaping national identity. Unlike European nations, which often tie identity to ethnic heritage, America, for good or ill, does allow for hyphenated identities, such as African-American or Mexican-American. In Austria, one is either Turkish or Austrian — there is no equivalent of a blended national identity. As a result, Turks and Austrians live as separate cultures rather than uniting around shared ideals. Over time, Austria’s future will not be determined by external threats but by shifting demographics within its borders.

America’s strength lies in its ability to forge a national identity independent of ethnicity. In theory, people from all backgrounds can participate in the American experiment, but assimilation does not happen automatically. If we continue to welcome immigrants, we must also provide the framework for integration — otherwise, we risk facing the same challenges Austria now confronts.